Pandemic-era air travel feels like a distant memory today, as we recall the days of strolling through quiet airports, listening to every suitcase roll, and boarding empty flights. Yet, the effects of these times are still highly pronounced today, and the Japanese domestic air travel market is one of them. Carriers in the nation have struggled to generate profits on domestic flights even as travel demand has bounced back.

Last week, four Japanese airlines gathered for a hearing regarding these ongoing struggles. The four included Skymark Airlines, Starflyer, Air Do, and Solaseed Air.

These airlines are categorized in Japan as “middle cost carriers” (MCCs), a unique term that isn’t found in much of the world. These carriers fill the space between full-service carriers, such as Japan Airlines and All Nippon Airways, and low-cost carriers, such as Peach Aviation or Jetstar Japan. Passengers can find reasonable prices that are in between these two airline types, reasonable onboard service with a beverage service, and seats with an acceptable amount of legroom and no IFE screens.

The Japanese domestic airline industry’s struggles span across most airlines in the country, but are particularly bad for these four carriers. There are three main contributing factors to these struggles, which are the following:

- Rising operating costs fueled by weak domestic currency

- Lower business travel demand after the pandemic

- Losing battles vs high speed rail

These three factors paint the picture for the changing landscape of Japan’s domestic air travel market. A further dig into these points shows that the future for the nation’s airlines is not a pretty one, and a change in strategies is inevitable.

Rising Operating Costs for Japanese Domestic Flights

For the most part, operating costs have risen for many industries all over the world since the pandemic, and the Japanese aviation industry is no different.

In May, Japan Airlines presented its data to the country’s transport ministry comparing pre-pandemic and post-pandemic costs, with fuel costs up 34%, maintenance costs up 70%, and aircraft costs, such as parts and material costs, up 38%. Overall, the airline is dealing with a 27% increase in total costs from FY2018 to FY2024. ANA also presented increases, with fuel costs up 19%, maintenance costs up 27%, and aircraft material costs up 29%.

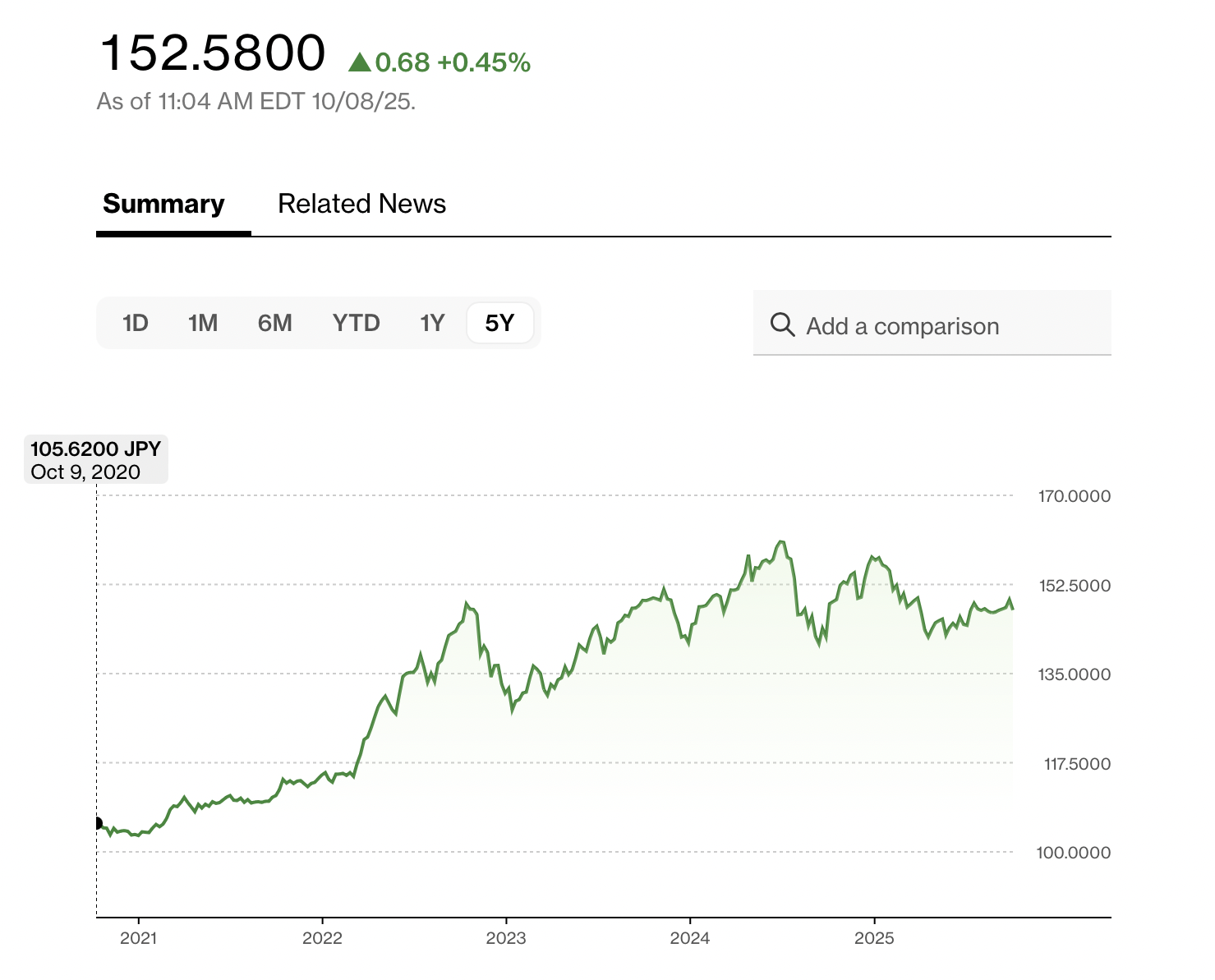

A big contributor to the rising costs for Japanese airlines is the weakening of its domestic currency. The Japanese Yen hovered around 100 JPY to 1 USD at the start of the decade, but has risen to 1 USD to 152.58 JPY as of Oct. 8, 2025.

Many transactions for Japanese airlines are made in US Dollars, such as investing in new aircraft orders, buying aircraft parts, and paying for labor and contracts overseas.

Take a brand new Boeing 737 MAX 8 with a 100 million USD price tag. With an exchange rate of 100 JPY to a dollar, the transaction would equate to 10 billion JPY. With today’s rate of 150 JPY to a dollar, however, that price tag increases to 15 billion JPY.

The most recent jolt for the Yen this week can be attributed to the introduction of the nation’s new Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi. Given that she supports a loose monetary policy, with interest rates kept low, a weak domestic currency can be expected to continue for now. Takaichi is a strong follower of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, from whom she draws a lot of her economic policies.

Of course, there are many other factors surrounding both the weak currency and rising operating costs, such as monetary policy in the United States and inflation in countries other than Japan. However, the conditions for a weak currency stemming from Japanese economic policy won’t be going anywhere for now, which is not good news for the nation’s airlines from an operations perspective.

Diminishing Business Travel Demand

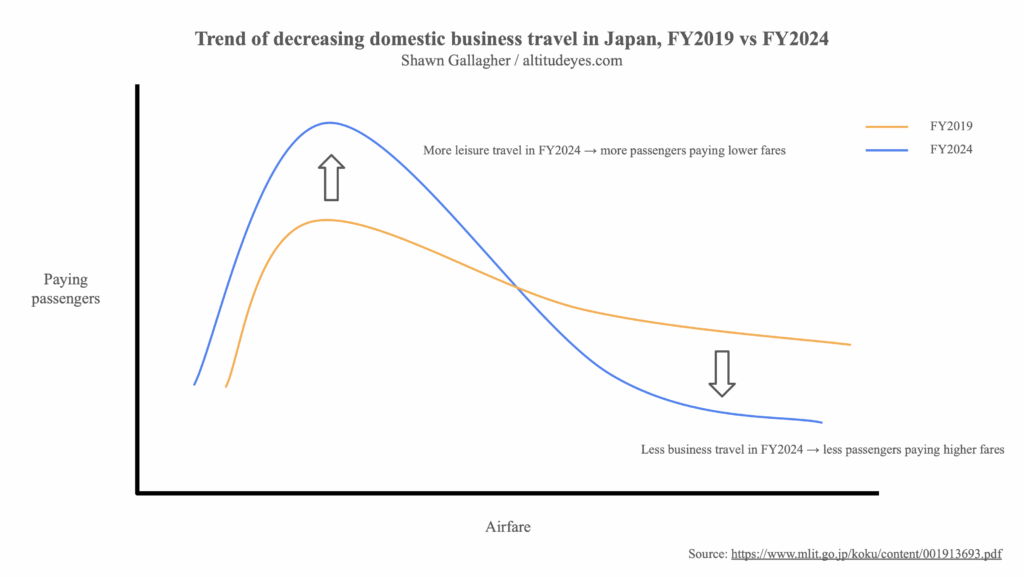

The diminished number of business travelers has been another major change in the domestic market since the pandemic. These passengers, who were responsible for much of the higher bucket fares for airlines, have gone away with remote work and online conferences becoming ever so common. ANA has shared that the airline is still at 76% of pre-COVID levels for its domestic business travelers.

In the meantime, airlines have done quite well with load factors, as most routes have returned to their pre-covid levels. Solaseed Air, for example, recorded a passenger load factor of 75% in 2024, the highest in the airline’s 28-year history. However, this alone hasn’t been enough for domestic routes to return to profitability.

With a smaller number of business travelers, Japanese airlines have been forced to run sales and sell more discounted fares to fill seats. As a result, carriers have sold more low-fare tickets while selling fewer high-fare tickets, which has decreased profitability in the domestic market.

Both full-service carriers and middle cost carriers have relied on business travel, and are struggling with the diminished demand.

Couple this with the rising operating costs, and the domestic air travel market is very grim. Japan Airlines states that while its domestic operations accounted for about 40% of its profits before the pandemic, it has now become unprofitable. Meanwhile, ANA has noted that a whopping 58% of its domestic routes were unprofitable in FY2023.

A Losing Battle Against the Shinkansen

These current conditions in this market aren’t pretty, and the future doesn’t look too bright either.

As Japan continues to improve its world-class Shinkansen service, airlines have been cornered into a difficult business that has seen a decreasing number of passengers every year.

In August, ANA announced a reduction of capacity between Tokyo Haneda (HND) and Komatsu (KMQ) airports. This reduction can be attributed to the launch of the Hokuriku Shinkansen to Kanazawa City in 2015 and a further extension in 2024. The airline previously served about 880,000 passengers in 2014, but now only serves about 360,000 annually a decade later.

This is just one example. Given that over the next decade or two, the country is expecting to see the Hokkaido Shinkansen extend to Sapporo, a speed increase of the Tohoku Shinkansen to 360kmh (224mph), and the opening of the Chuo (Maglev) Shinkansen with trains at 500kmh (310mph), there’s not a lot of wiggle room left for the airlines in the coming years.

Even if flying can offer somewhat of a competitive travel time against a Shinkansen route, airlines also have to match the cost of the Shinkansen. This makes it harder for them to turn a route into a profit, as it’s harder to pull a passenger into a last-minute purchase on a high fare.

The Future of Domestic Air Travel in Japan

The higher costs and lower business travel demand are a strain for Japan Airlines and ANA, but there are still ways to get around it with their international and cargo operations.

Although the weak Japanese Yen is a negative for operational costs, it has the benefit of encouraging inbound tourism. Japan recorded a record 22 million foreign tourists in the first half of this year, which translates to a lot of demand for JAL and ANA’s international flights.

Going forward, Japan Airlines aims to increase the proportion of its overseas passenger arrivals that are fed into its domestic operations. Although this won’t fully eliminate the issue of low business travel demand, this will help the airline support its local routes, such as flights to Tohoku, which are in particularly bad shape.

ANA is looking to take a similar strategy with foreign visitors, and may also increase prices for business travelers to make up for the smaller number of business travelers.

The situation is more dire for the four “middle cost” carriers of Skymark Airlines, Starflyer, Air Do, and Solaseed Air. Unlike JAL or ANA, none of these airlines have significant international operations, meaning they are in a difficult position to directly benefit from the rising number of foreign visitors.

Skymark Airlines tried, but went bankrupt in 2015. Starflyer had a bit of an international presence in South Korea and Taipei before the pandemic, but neither destination is operated by the airline today. Meanwhile, Air Do and Solaseed Air have never ventured overseas.

Given the grim reality of Japan’s domestic air travel market, it perhaps makes more sense to look for growth on short-haul international routes within East Asia, but breaking into many of these markets might be too late today.

Low-cost carriers such as Peach Aviation, Jetstar Japan, T’way Air, Spring Airlines, and others already dominate this market. Not only do they connect major cities like Tokyo, Seoul, and Shanghai like the full-service carriers do, they also have good coverage over local, smaller destinations. For the four Japanese middle-cost carriers, breaking into these markets will now be a challenge with all of the low-cost airlines having established their presence, and attempting to capture demand amidst all of the preexisting service could be a doomed strategy.

Additionally, since low-cost carriers are generally less reliant on business travelers, the lack of business travelers since the pandemic has been less of an issue.

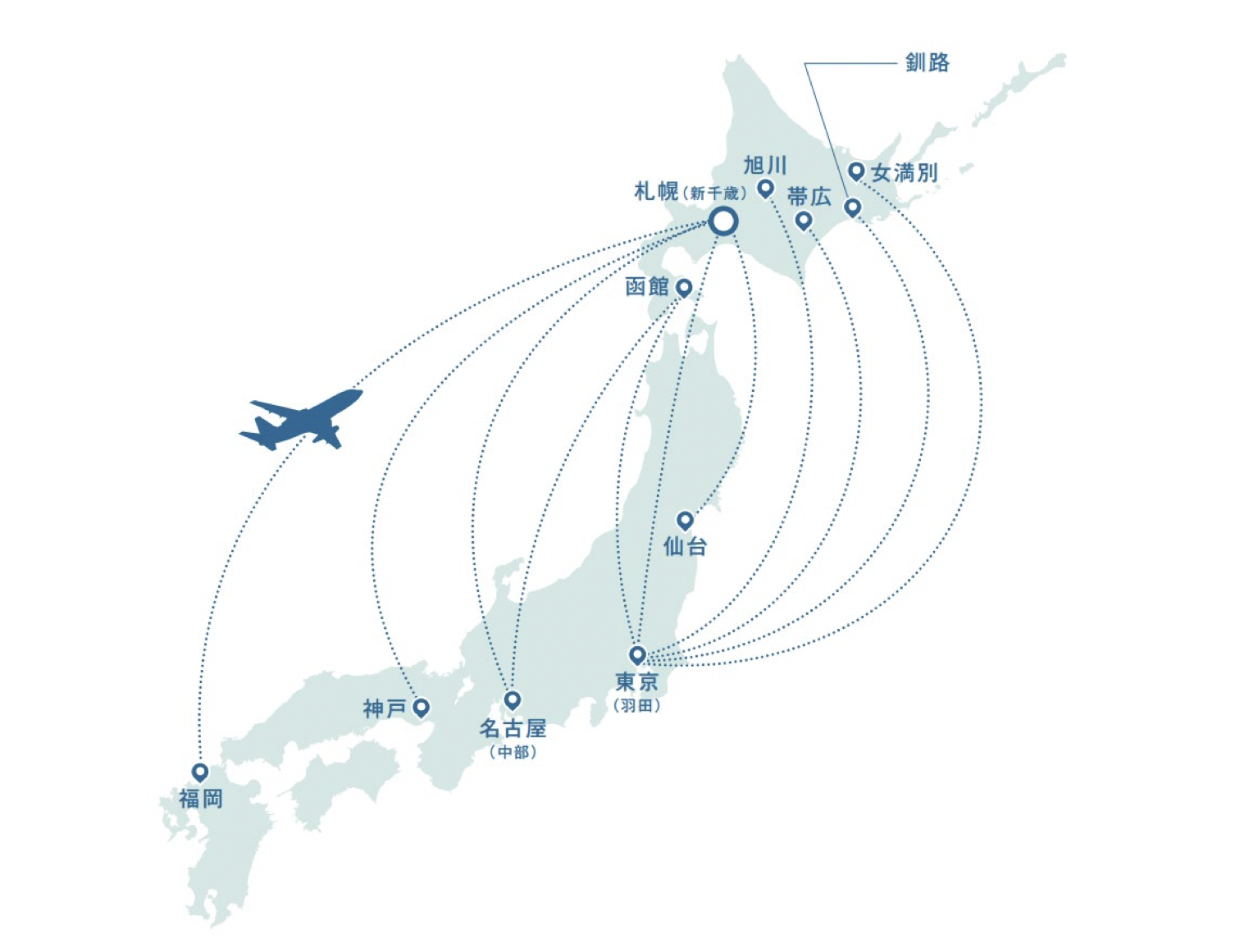

Below is Air Do’s route network. The airline is based in Hokkaido, connecting the island to the rest of Japan.

Compare this to Peach Aviation’s route map, one of Japan’s low cost airlines, below:

Granted, these are two very different airlines with different business models (ANA has majority ownership of Peach). But when searching for success today as an airline not named JAL or ANA, given that Peach returned to profitability in 2024 and continues to expand across East Asia and Southeast Asia, the differences are hard to ignore.

There’s no question that the unique business model of Air Do and other “middle-cost” carriers, offering a good balance of reasonable prices with reasonable service, has been popular in Japan. However, their unwillingness to do anything aside from serving the same routes they had served within the country for the last two decades has come back to bite them. Valuable Haneda Airport slots continue to go to the same, unprofitable routes today, all while costs continue to rise, making it difficult to invest in future aircraft and operations.

Air Do’s handcuffed situation, for example, can be traced to the airline’s full usage of its 12 aircraft that make up its fleet, leaving no room for growth. This is complemented by heightened price tags from the weak currency, creating a difficult condition for investing in its future fleet. This double whammy puts the airline in a dire situation for future change and growth.

Nothing ever stays the same forever, especially in the aviation industry. Major events such as the September 11 attacks, the 2009 recession, the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, and the COVID-19 pandemic happen every once in a while, and consistently change the industry as a whole. It is perhaps imperative to be flexible and prepared in an ever-changing industry, and this value has remained on display for Japanese airlines since the pandemic.

Today, the overall lack of room for growth in the Japanese domestic air travel market is an unfortunate reality for the nation’s carriers. With the grim future of Japanese domestic air travel, the future of Japan’s middle-cost carriers, Skymark Airlines, Starflyer, Air Do, and Solaseed Air, may be in jeopardy without major changes.

Featured image by the author.